The Lark Ascending and Other Birds

- Graham Abbott

- Mar 30, 2020

- 6 min read

There is something quite magical about birdsong. The infinite variety of sounds produced by birds has put them in a special category as far as we humans are concerned. We prize birds for their singing, and most birdsong is regarded by us as beautiful. It only stands to reason therefore that birds, which produce sounds we interpret as musical, should inspire the musical sounds produced by humans.

The other magical thing about birds - their ability to fly - has also been reflected in music. In this article we’re going to look at some pieces, famous and less well-known, which take their inspiration from birds.

Jean-Philippe Rameau was inspired by a bird in one of his better-known harpsichord works. Dating from around 1728, it's called La Poule (The Hen), and it’s one of the earliest instrumental pieces to take the programmatic representation of an animal quite so literally into the world of music. The clucking of the hen and its scratching can be heard very clearly in the repeated notes and the rapid upward arpeggio which follows them .[listen]

Two hundred years later, in 1928, the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi used Rameau’s hen in his suite Gli uccelli (The Birds). This suite is based on music of a number of Baroque composers, but adapted and orchestrated in Respighi’s own colourful manner. The obsessive clucking and scratching is if anything highlighted in this later view of the music. [listen]

In modern English we use the term “swansong” to refer to a person’s last piece of work or farewell performance. This is derived from the old legend that the swan, which has no beautiful song during its life, sings beautifully at the moment of its death.

The English composer Orlando Gibbons is believed to have penned not only the music but also the words to his famous madrigal The Silver Swan, which was published in 1612. The description of the swan’s song of death is seen by some as Gibbons’ farewell to the madrigal itself, which was increasingly out of fashion by the early 17th century. [listen]

The silver swan who living had no note,

when death approached unlocked her silent throat;

leaning her breast against the reedy shore

thus sung her first and last, and sung no more:

“Farewell all joys, o death come close my eyes,

more geese than swans now live, more fools than wise.”

An English composer of a later generation, Benjamin Britten, used birdsong as the basis for one of the audience participation songs in his 1949 children’s opera The Little Sweep. The audience is taught the song before the performance, and then in the course of the action is invited by the conductor to sing with the onstage characters. The audience in the Night Song is divided into four parts, each of which sings about a different bird, complete with birdsong imitations; we hear the owl, the heron, the turtle dove and the chaffinch. After singing separately, the four parts combine. It’s Britten at his most charmingly direct, something which comes across well in his 1955 recording. [listen]

Mozart included the song of his pet canary in the middle section of one his late set of German Dances, K600. I can imagine him being driven to distraction while trying to compose at home with this perpetually going on in the background, so maybe this was his way of reaching some sort of truce with the poor bird. In this YouTube video, the fifth dance begins at 7'55, and the trio with the canary song starts at 8'35. [listen]

Seventeen years later, in his sixth symphony, Beethoven concluded his musical depiction of the scene by the brook with references to birdsong. Beethoven named the birds in the score - the flute is the nightingale, the oboe is the quail and the clarinet the cuckoo.

The cuckoo’s of course is probably the easiest birdsong to replicate in music, with two clearly identifiable notes in a descending pattern. Beethoven’s clarinet cuckoo is a perfect example. Another clarinet can be heard in Saint-Saëns' Carnival of the Animals. [listen]

180 years after Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, the Hungarian-born composer György Ligeti wrote one of his nonsense madrigals, The Cuckoo in the Pear Tree. It takes the cuckoo’s call to lengths Beethoven and Saint-Saëns would never have imagined. [listen]

The Cuckoo sat in the old pear-tree, Cuckoo!

Raining or snowing, nought cared he. Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo, nought cared he.

The Cuckoo flew over a housetop high. Cuckoo!

"Dear, are you at home, for here am I? Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo, here am I."

"I dare not open the door to you. Cuckoo!

Perhaps you are not the right cuckoo? Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cukoo, the right Cuckoo!"

"I am the right Cuckoo, the proper one. Cuckoo!

For I am my father's only son, Cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo, his only son."

"If you are your father's only son - Cuckoo!

The bobbin pull tightly,

Come through the door lightly - Cuckoo!

"If you are your father's only son - Cuckoo!

It must be you, the only one -

Cuckoo, cuckoo, my own Cuckoo!

Cuckoo!"

In the early 1920s, Respighi (from whom we heard earlier) wrote his massive orchestral showpiece The Pines of Rome. In this he did something rather radical for its time: he had a gramophone recording of birds played during a section of the music, even going to the extent of listing the record number in the score. Half a century later the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara went a step further. In his Cantus arcticus (Song of the Arctic), Rautavaara went into the northern arctic marshlands himself, armed with a tape recorder, and incorporated recordings he made of birds into the score. He even listed the birds themselves as the soloists in this “concerto for birds and orchestra”. This YouTube video has the entire work plus the score. [listen]

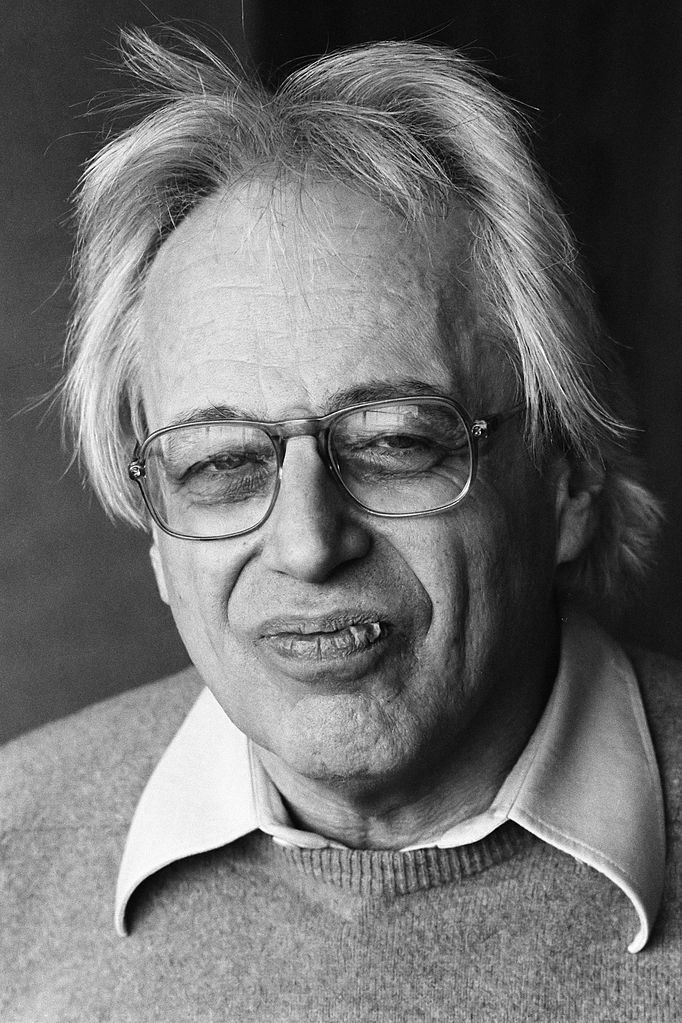

Perhaps no other composer of the 20th century pursued birdsong like Olivier Messiaen. From the 1950s he started collecting, notating and adapting actual birdsong into his compositions. He once said, “the birds are the real artists - they are the true originators of my pieces.” Almost all his works in the last 35 years of his life contain birdsong in one form or another, but in major bird-inspired works like the massive Catalogue of the Birds he showed himself obsessed with and immersed in birdsong in a way unmatched by any other composer.

Here is Messiaen’s representation of the sky lark in a composition written seven years before his death, called Little Sketches of Birds. [listen]

Messiaen’s vision of the lark started with its song. In 1914, the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote a work about the lark which inhabits a very different world, and which took as its starting point a poem. Rather than focusing on the song of the lark, Vaughan Williams focuses on its flight. The title of this miraculous piece - The Lark Ascending - is the title of a 124-line poem by the English poet George Meredith. Vaughan Williams prefaces his score with 12 lines from the poem, and the result is a work for solo violin and small orchestra which encapsulates not only the distant airiness of the lark’s flight, but also Vaughan Williams’ own pastoral style.

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake...

For singing till his heaven fills,

‘Tis love of earth that he instils

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup,

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes...

Till lost on his aerial rings

In light - and then the fancy sings.

Vaughan Williams called The Lark Ascending a “Romance for violin and orchestra”. Calling it a Romance immediately makes us think of works like the Beethoven Romances for violin and orchestra, and other nineteenth century “characteristic” pieces. But Vaughan Williams moves far beyond any mere sentimentality in this work. In describing the soaring flight of the lark, he takes us into a world far removed from the world, a timeless state of being simultaneously lost and fulfilled.

Structurally the piece is in ternary form, with the first A section beginning and ending with a soaring solo for the violin. The B section begins with a melody in the woodwinds which is reminiscent of English folksongs, and the music of this section has more forward momentum than the earlier section. Gradually the melody and mood of the opening A section takes over, and the piece ends with the violin soaring alone into the air, out of sight, into silence.

This really fine ABC Classics performance of The Lark Ascending was made in Sydney in 2002, and features Dimity Hall as the violin soloist. Sinfonia Australis is conducted by Antony Walker. [listen]

This article is based on a Keys To Music program first aired on ABC Classic FM (now ABC Classic) in January, 2005.

Comments