The Life and Work of Frederick Delius

- Graham Abbott

- Nov 27, 2020

- 11 min read

Music is an artform which doesn't easily fit into pigeon holes. This doesn't stop us trying, though, and it has to be admitted that our brains need to organise and categorise all sorts of things to make sense of them. But sometimes a composer comes along who doesn't fit easily into a category and whose music is not widely-known. Such a composer is the subject of today's post; his name is Frederick Delius.

Fritz Theodore Albert Delius was born in the English city of Bradford on 29 January, 1862. His parents had migrated from Germany and had already taken British nationality twelve years before Fritz - the fourth of their fourteen children - was born. His father, Julius, was a successful wool merchant. Even though the household was musical, and young Fritz studied piano and violin, there was no question that the boy would have anything other than a business career; music was out of the question.

Delius's youth was marked by clashes between his family expectations and his desire to immerse himself in music. He was apprenticed to the wool trade and travelled abroad frequently in the course of these duties, but he often neglected his work in order to attend musical performances or have lessons.

In 1884 Delius went to the United States to manage an orange plantation near Jacksonville, Florida. Whether this was his father's idea, or his own, is unclear, but it didn't take long for it to become obvious that away from the control of his father, Delius had no intention of devoting himself to the plantation, but rather used his time and resources to learn more about music. In Florida - where he confessed himself deeply moved by the singing of African Americans - he had lessons in counterpoint and composition with Thomas Ward, training he later said was the only useful musical instruction he ever had. He soon left a caretaker in charge of the orange plantation and moved to Danville, Virginia to start a working as a music teacher.

Delius had only been in the US about a year before his father relented and allowed him to embark on a musical career. With his father's financial support, he went to Germany to study at the Leipzig Conservatory, and spent two years there from 1886 to 1888. In Leipzig he made little headway academically, but he was immediately at one of the major centres of European music. In the 1880s, Arthur Nikisch and Gustav Mahler were conducting opera in Leipzig, and Brahms and Tchaikovsky were among those who conducted at the Gewandhaus. One of the most important influences on Delius was the violinist Hans Sitt. Delius had had violin lessons with Sitt during his European travels before going to America. Now in Leipzig they made contact again, and in 1888 Sitt arranged a trial performance of Delius's first orchestral work, the Florida Suite. This the work's second movement, called "By the River". [listen]

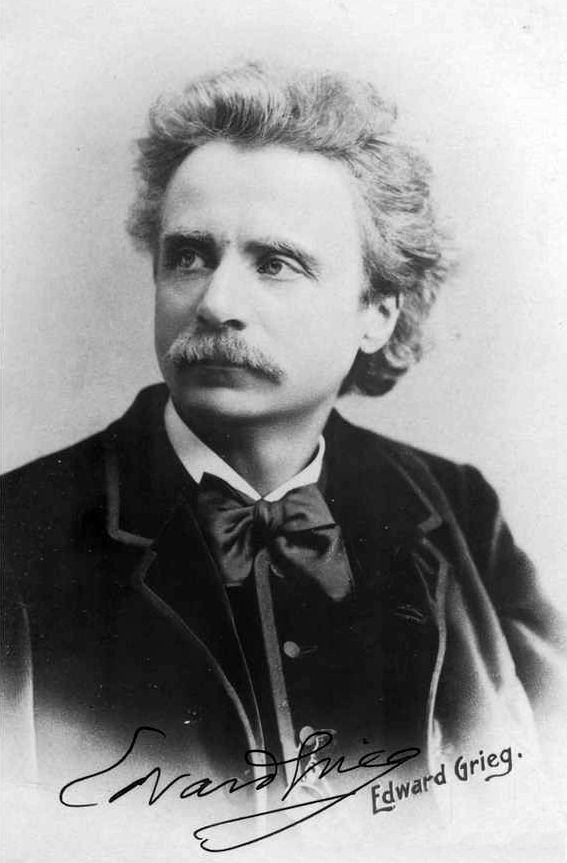

Even more important to Delius's development was establishing a friendship with Edvard Grieg during his Leipzig years. They were introduced by the Norwegian composer Christian Sinding, and Delius had already developed a strong affinity for Norway in his earlier European travels. Grieg became a strong supporter of Delius during these vital early years.

In 1888 Delius left Leipzig and moved to Paris. His social circle expanded to include many famous names, August Strindberg, Edvard Much, Paul Gaugin, Gabriel Fauré and Maurice Ravel among them.

Delius's Paris years were highly productive. He produced two operas, Irmelin and The Magic Fountain, and his symphonic poem On the Heights (sometimes known by its Norwegian title of Paa Vidderne) was performed in Norway in 1891 and Monte Carlo in 1894. [listen]

Another work from the Paris years was the fantasy overture Over the Hills and Far Away, written between 1895 and 1897. The premiere performance took place in Germany in 1897 under the baton of Hans Haym, a conductor who became part of a growing circle of Delius supporters. [listen]

In the same year as the premiere of Over the Hills and Far Away, 1897, Delius met and began a relationship with the painter Helene Rosen, known as Jelka. They shared her house at Grez-sur-Loing near Fontainbleau and in 1903 they married. Shortly before his marriage he Anglicised his first name to Frederick, having been known as Fritz Delius for the first forty years of his life. Apart from a short period during the first world war, Delius spent the rest of his life at Grez. Indeed, for a composer even today regarded as English, he actually spent relatively little of his life in the country of his birth.

In addition to Haym, another conductor who supported Delius's work around the start of the 20th century was Alfred Hertz. In 1899 Hertz conducted an all-Delius concert in London which included excerpts from his most recent opera, Koanga (which would not be staged in full for another five years). Koanga harks back to the composer's days in Florida, with its tragic story drawn from the deep South. The orchestral dance La Calinda is an excerpt sometimes heard in isolation from the opera, but as a whole, Koanga is a work which deserves to be better-known. This is the very end of the work. [listen]

One of Delius's most important orchestral works dates from the same period. Called Paris, this tone poem is subtitled "Song of a Great City". Its premiere was conducted by Haym (to whom it's dedicated) in 1901 and the work provoked some negative critical comment. The Grove article on Delius describes Paris as displaying strong influences of Richard Strauss, influences which never again made their presence felt so obviously in Delius's music. The work is a multi-sectioned nocturne, full of music suggesting Parisian nightlife and the intimacies of lovers. [listen]

Immediately after Paris came what is one of Delius's most famous works, even if only a very small part of it is played with any regularity today. The opera A Village Romeo and Juliet was written between 1899 and 1901. It tells the story of two young lovers whose happiness is thwarted by feuding families and local gossip. They decide to spend one day together then end their lives. The orchestral interlude from the opera - The Walk to the Paradise Garden - is often heard as a stand-alone piece [listen], but the opera's tragic ending - where the lovers float on a barge into the river and sink it, drowning together - is described in Grove as being "some of the most exquisite music written for the stage". [listen]

In the 1880s and 90s Delius's major works had tended to be orchestral tone poems and operas. In the first decade on the 20th century his attention shifted to choral works and - after a few years - chamber music and concertos. The choral works include two of his largest creations, Sea Drift and A Mass of Life. Sea Drift is regarded by many as Delius's greatest achievement, and its premiere in Essen in 1906 (the same year and city in which Mahler's sixth symphony had its premiere) was a huge success for the composer. It's scored for baritone, chorus and orchestra and sets Walt Whitman's poem describing a boy's reaction to witnessing the grief of a sea bird which has lost its mate. The music is direct yet tender, flowing seamlessly from one section to another and using a harmonic language which is effective and beautiful. The ending of Sea Drift has long been one of my favourite things, setting Whitman's heartbreaking words: "O past! O happy life! O songs of joy! / In the air, in the woods, over fields, / Loved! loved! loved! loved! loved! / But my mate no more, no more with me! / We two together no more." [listen]

The premiere of Sea Drift helped secure Delius's reputation in Germany. A Village Romeo and Juliet had its premiere in Berlin the following year and in 1910 Brigg Fair was performed by no less than 36 different German orchestras. Before that, though, Delius created another massive choral work, A Mass of Life. This is not a setting of the Latin Mass, but is based on Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra. As such it immediately invited comparison with Richard Strauss's famous orchestral tone poem, written a little over a decade before, but the similarities go little beyond the literary inspiration. Delius claimed to intensely dislike Strauss's work, and A Mass of Life inhabits a rather different musical world altogether. A Mass of Life had been given incomplete performances in Germany and England in 1908; Sir Thomas Beecham gave the first complete performance in London in 1909. [listen]

Sea Drift and A Mass of Life were followed by another orchestral choral work, Songs of Sunset, in 1907. In the years following Delius turned to smaller-scale works, creating smaller but no less impressive or beautiful music in the process. The orchestral tone poems Brigg Fair and In a Summer Garden date from 1907 and 1908. They epitomise what most people tend to think about Delius - a sweet, tranquil, lyrical voice, superbly crafted and inhabiting an individual sound world. Brigg Fair was inspired by Percy Grainger's choral arrangement of the Lincolnshire folksong of that name. Delius's orchestral work - a set of variations on the same tune - is called an "English Rhapsody". The result is one of those works which make us forget how little of his life Delius actually spent in England. [listen]

Yet the works which followed Brigg Fair and In a Summer Garden are comparatively neglected these days, and this has led to a misunderstanding of the breadth of Delius's stylistic range (a similar thing could be said about the music of Delius's contemporary, Ralph Vaughan Williams). Three works from later in the second decade of the century, for example, create a very different impression. The Song of the High Hills (completed in 1912), the North Country Sketches (completed in 1914) and Eventyr (from 1917) are less predictable and contain evidence of a darker side. The "Winter Landscape" from the North Country Sketches is a good example. [listen]

In the midst of these works came Delius's final opera, Fennimore and Gerda, the work which in Grove is said to have initiated this later style in Delius's output. [listen] The piece draws on Delius's lifelong love of Scandinavia and is the composer's attempt at a contemporary conversation piece, a style he described as "short, strong emotional impressions given in a series of terse scenes". It was first performed in Frankfurt in 1919.

While moving into new stylistic areas in the years before the first world war, Delius didn't completely abandon his sweeter, more intimate style. Two orchestral works from 1911 and 1912 embody his more familiar sound world, and one of them, On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring, is one of his best-known creations. [listen]

After a career of writing works with either narrative or programmatic content, it comes as a shock to encounter Delius in 1914 - aged in his 50s - suddenly changing direction and coming to terms with absolute music, in particular chamber works and concertos. The first violin sonata (begun in 1905) was completed in 1914 and followed by two concertos. The double concerto for violin and cello was completed in 1916, and the violin concerto was written the same year. [listen]

In addition to these concertos, he also wrote a cello sonata and a string quartet in 1916. Both works have much to recommend them and their comparative neglect isn't justified. This is a fine recording of the quartet. [listen]

Yet Delius's focus on smaller-scale music during the first world war was only part of his creative output at the time. At the same time he worked on a very large-scale choral work, perhaps his least known: Requiem for soprano, baritone, chorus and orchestra. Like his contemporary Gustav Holst, Delius held unconventional beliefs. Requiem is not a setting of the usual liturgical text of the Mass for the Dead, and the misleading title was sometimes amended by Delius when he referred to is as his "Pagan Requiem". It sets a text which the composer describes as pantheistic, preaching courage in the face of death and finding consolation in the cycles of nature. It was dedicated "To the memory of all young Artists who have fallen in the war".

The original German text was long thought to have been compiled by Delius himself, but subsequent research has shown it to be largely the work of Heinrich Simon, a friend of the composer who was a talented musicologist and writer. It is baldly anti-religious and pro-humanist, derived from Nietzsche, Ecclesiastes and elsewhere, and this has served to alienate many who are offended by this stance. But whatever one's views of the text, the music Delius created for its setting is magnificent, and in some parts unique in his output. It is a work completely undeserving of its obscurity.

The magnificent final movement contains elements of bitonality, inspirations of Balinese music, and offstage brass in its celebration of the recurrence of springtime, a focus on the "reality of life" as opposed to the "tale of falsehoods". It's music which embraces all. This recording uses Philip Heseltine's English translation. [listen]

After the first world war, Delius's health steadily declined. It's generally believed that he had contracted syphilis in Paris around 1895, not long before he met Jelka, and the effects of this became increasingly debilitating from around 1916. From 1920 he found it difficult to hold a pen and Jelka Delius was involved increasingly in helping with his correspondence.

The last work he composed without the assistance of others was the incidental music to James Elroy Flecker's play Hassan. This ran for 281 performances in London and was Delius's greatest commercial success during his lifetime. But by the time the play opened, in September 1923, the composer was very ill, and he had to be carried into rehearsals. Philip Heseltine (better known by his pen name of Peter Warlock) assisted Delius during this time and soon after wrote the first account in English of Delius's life.

But Delius himself became increasingly unwell, with blindness and paralysis gradually worsening. His frustration at being unable to finish a number of works must have been immense, given the fact that his mental faculties were unaffected. He eventually accepted the offer of assistance from a young English musician called Eric Fenby. Fenby had admired Delius's music for some time and from 1928 became his amanuensis.

After the composer's death, Fenby dedicated much of the rest of his life (he died in 1997) to championing Delius's music. A fascinating talk by Fenby on Delius can be heard on YouTube, starting here.

Fenby helped Delius complete a number of his unfinished works. One of these was Cynara, a setting of Ernest Dowson's poetry for baritone and orchestra. This was originally intended to be part of the Songs of Sunset, the third of the great trilogy of choral works which included Sea Drift and A Mass of Life. However Delius had left this section unfinished in 1907 and removed it from the earlier work. Fenby discovered it and helped the composer complete it as a stand-alone piece in 1929. [listen]

In his final years Delius had the joy of seeing no less a figure than Sir Thomas Beecham champion his music. Beecham organised a Delius festival in 1929 comprising six concerts, all of which the ailing composer managed to attend. He received honours towards the end of his life as well, including the Companion of Honour, and the Freedom of the City of Bradford, his birthplace.

But Grez had been his home for three decades and it was to Grez Delius returned for his final years. He remained stoic during his final illness and took great comfort from hearing recordings and radio broadcasts of his music. He died at Grez on 10 June 1934. His wish was to be buried there but the authorities refused permission. He was eventually buried in England, at Limpsfield in Surrey, in 1935.

Frederick Delius is a composer whose music most categorically deserves a fresh look. The fact that he doesn't easily fit into a niche - such as romantic or modern or impressionist - has made him too hard for some to approach. But there is no doubt he was an individual, creative, masterful composer whose music takes the endless melody and orchestral mastery of Wagner and the warmth and touching directness of Grieg and somehow manages to make a new musical world from their synthesis. I hope this survey inspires you to listen to more.

This article is based on a Keys To Music program first aired on ABC Classic FM (now ABC Classic) in May, 2012.

Comments